I often see Facebook images and articles about social issues and share them on my own timeline , but I don’t think I can share this one. It’s not that I don’t agree with the sentiment behind it.

, but I don’t think I can share this one. It’s not that I don’t agree with the sentiment behind it.

Let me start by saying that I support people of retirement age getting an appropriate pension. It’s a part of human decency in supporting society. Not least as, after forty years of working myself, my own retirement is on the near horizon.

This image came with the comment that ‘inept governments who did not invest wisely over the years shouldn’t blame the olds’. But it’s not as simple as that. Firstly we elected those inept governments and then put our trust in them to act in our best interests. At one time we genuinely believed they did, now as a society we are much less sure (NatCen’s British Social Attitudes Survey highlights just how much our trust and belief in our governments have declined over the years).

But did our governments act ineptly in this matter? Surely governments over the years (1) could never invest the money because it was always paying out this year’s pension with this year’s Tax and National Insurance income and (2) why should they because in the early days of pensions they could reasonably assume that it would always be possible to work that way. Isn’t that how the majority of us budget our own weekly or monthly income?

They didn’t have a crystal ball any more than the rest of us to see how technology and globalisation would change the world. And so for all sorts of reasons that balancing of the budget between pension income and pension outgoings became harder and so in recent years we have seen the promotion of the private pension provision and the raising of the retirement age. That doesn’t take into account the fact that there are only so many jobs in the market place and if the old are working then the young aren’t – but that’s another debate.

In the meantime there are some things for which we should still be grateful – the UK state pension has only existed for 106 years and when it was introduced in 1909 it was as a non-contributory but means tested benefit claimable only over the age of 70 when only 25% of the population lived long enough to claim it. And, due to poor working conditions and health, many of those who did reach 70 years of age would have been among the better off and so not entitled to a means-tested benefit. Before 1909 you went to the workhouse or died if your family couldn’t keep you if you couldn’t work for any reason. (for more detail see History of State Pension Age)

When the new contributory pension was introduced in 1925 this was still an era when married women did not work. Men became entitled to pension payments at the age of 65 but had to wait until their wife retired, often 4-5 years later, to receive the full couple’s entitlement, forcing them either into poverty or the wife into the impossibility of entering the workplace, some for the first time in 40 years. Fortunately in those days employability depended less on employment record, although she would still have faced the barrier of married women not being seen as needing employment. This was no doubt harder on the women of the middle classes at the time as the women of the working classes were more likely to have had to supplement the family income through domestic work, taking in laundry, ironing and mending, and could continue to do so.

Women didn’t work outside the home because that was the social norm. A young woman might begin working when she left education but when she married she was often forced to resign her job to allow that opportunity to be passed on to another young person. My own mother was forced to resign her job in a local pharmacy when she married in the mid-1950’s as she was now perceived to be the ‘responsibility’ of her husband. But her husband was a manual labourer and on low income and not earning enough to keep the two of them. One day when my mother went into the pharmacy she was talking to her old boss and said how hard it was. He offered her her old job back – on the condition that she was called Miss, used her maiden name at work and took off her wedding ring at work: he feared the disapproval and that he would lose customers if they thought he was employing a married woman. As a carryover from that time, when I married in 1981 my new aunts (all in their 70’s) were shocked and disapproving that I intended to continue working once married.

In the meantime, in this same cultural environment, when the retirement age for women was reduced to 60 in 1940 it allowed couples to receive their pension entitlement at approximately the same time, based on the average age differences between husbands and wives, reducing pensioner poverty but with the happier side effect of allowing long term marrieds to retire and spend their last few years together, particularly as men were still likely to die of old age before their wives retired before that time.

Of course the second world war (1939-1945) did a lot to change the culture then, with married women making up the backbone of the domestic workforce while so many of the men were away fighting in the war. Expectations changed and with the end of the war things were never the same again.

The continued changing nature of society and relationships, powered by technological developments and globalisation, has changed our society almost beyond recognition to those times and things like the age differential has ceased to seem quite so defensible, allowing for legislative changes for men and women’s pensionable ages to be increased and brought on a par again.

Finally, with improved health care for everybody under the NHS, far more people have been living longer not only to reach pensionable age but also to be entitled to a pension income for half as long again as they worked and contributed for, thus increasing the burden on those still working and contributing. Back to my own mother’s story: thanks to the generosity of her employer she was able to work full time for around 8 years between leaving school and giving birth to me. Thanks to a local employer who specialised in exploiting young mums in need of an extra income she was able to work part time for a further 11 years. Then she worked a further 12 years full time until she retired at the age of 60. Had she not retired at 60 she would not have been able to work for much of the next five years as she underwent two hip replacement operations, one of which took much longer to heal than normal, due to infection. On a low income or working part time for 31 years, it is questionable whether she could ever have invested enough in her working life to have funded what is already over 23 years of retirement. Why should I consider a government capable of doing that (as suggested by the commentator I quoted at the beginning of this article)? For comparison, my own pension arrangements include two private company pensions now invested in private insurances that represent 10 years of working life and a combined anticipated income of £70 per month. If that is representative of the potential investment over 50 years I would have £350 per month to look forward to – less than the rent on a one bedroom flat. The rest of my private pension entitlement is better for having been with a local government pension scheme for a number of years but since halved due to divorce and a compulsory pension sharing agreement, just one of the newer challenges faced by today’s pension investors and not anticipated by the original pension planners 100 years ago, and still, in my case, not enough to pay the rent on a one bedroom flat. Admittedly I started late, having been born into the generation that was still being told our National Insurance contributions included an investment for our pensions. For all governmental intentions, private sector pensions are never going to fill the Welfare Benefits gap.

Like most people of her age, my mum could not work if she wanted to. She may have lived well beyond the life expectancy of a woman at the beginning of the 20th century, when pensions were introduced, but like so many of her friends, it has not been in the kind of health that would have enabled her to compete in the workplace.

The fact is, when life expectancy means that retirement is going to last for as much as half as many years again as we are able to work (more if you add a long university education in to the equation), governments need to budget for an aging population that is based on more than ‘investing wisely’ what is paid in National Insurance contributions.

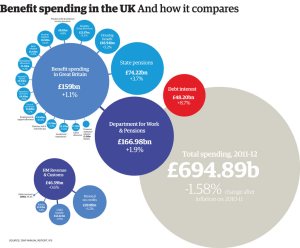

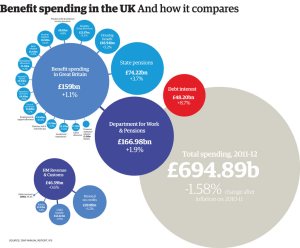

In 2011-12 pensions and pension credits amounted to £82.33b, almost double what was spent on disability benefits combined (£24.58b) and almost a third of the total welfare benefits bill; although neither figure takes into account Housing and Council Tax Benefits, which will somewhat increase both these figures and their proportion of the overall benefits bill. These are not figures that can be easily changed. Age and disability cannot be ‘undone’. And ironically a capitalist society needs a pool of unemployed people to keep wages in check and provide incentives to workers to conform.

In 2011-12 pensions and pension credits amounted to £82.33b, almost double what was spent on disability benefits combined (£24.58b) and almost a third of the total welfare benefits bill; although neither figure takes into account Housing and Council Tax Benefits, which will somewhat increase both these figures and their proportion of the overall benefits bill. These are not figures that can be easily changed. Age and disability cannot be ‘undone’. And ironically a capitalist society needs a pool of unemployed people to keep wages in check and provide incentives to workers to conform.

Some things might be changing. Concerns over the impact of the rising incidence of diet related health problems, including obesity, diabetes, heart problems, and more, have raised the possibility of a lowering of the average lifespan. The very real issue of antibiotic resistance, compounded by use of antibiotics in intensive farming methods and reduced research into new antibiotics under the growth of privately funded medical research where antibiotic development is not profitable, will have the same impact.

While the mercenary view suggests this will reduce the pressure on pension provision in the future it will hardly help the wider financial picture as pressure is put on health providers and disability benefits, while reducing the pool of people available to work.

Emotive photos with captions that pensions are not a benefit but something that has been paid for over years is sound-bite propaganda. It’s not helpful in the wider debate. We are collectively a part of a wider community. Bunkering down into our own field of concern, whether it be pensions, disability benefits, child poverty, NHS, or education, will not help. The creeping privatisation of our National Health Service and Education system (through increasing academies) will not produce an answer. Just as communism fell because of the greed of a minority and the oppression of the majority, so too will capitalism eventually follow for the same reasons.

The whole system needs an overhaul. Society as a whole needs to recognise shared responsibility for the functioning of society. That includes the domination of our food industry by companies that put profit before community health (and global impact); the impact of the privatisation of research that means that essential but unprofitable research doesn’t get done; the privatisation of healthcare that will disadvantage the already disadvantaged (just look to the United States to see why the NHS should be saved); the privatisation of education and social care that means that costs and services have to meet the needs of shareholders often at the expense of service users, because that’s how capitalism works; governments that make policy decisions based on short term objectives, or what will get them voted in again next time, because that’s how democracy works, instead of on what society needs five generations into the future, as the old American Indians thought.

I have become a fan of Margaret Heffernan’s book Wilful Blindness (she’s also on TED Talks). Its human nature, it’s in the way our brains have been wired, to see only that which is easy to see. Facebook works that way: ever noticed how you always get more of what you believe, that’s because facebook works like your brain and ignores that which you will find intellectually uncomfortable. But we have to make the effort to see beyond the natural blindness, to see beyond the soundbites, if we ever want to be a part of a fully functioning society that cares for one another.

Posted in

Miscellaneous,

Moralities,

Political,

Social and tagged

capitalism,

culture,

democracy,

education,

government,

health,

history,

NHS,

pensions,

politics,

poverty,

responsibility,

society,

soundbites,

welfare benefits |